Review: Dora Maar

Like so many women throughout history, Dora Maar is best known for her connection to a more famous man. For many art historians, she’s a footnote in the biography of Pablo Picasso, one of many young women the creepy cubist collected throughout his life.

But this is 2019: if Picasso were around today he’d be cancelled quicker than you could say “stop having sex with teenagers”, and Maar’s work is worthy of this retrospective on its own merits.

She started her photography career in the early 1930s, an exciting time for a medium in demand from both the printed press and a legion of ad-men. Maar could do it all. Her dynamic fashion shots, full of movement and shadow, wouldn’t be out of place in the September issue of Vogue. Her reportage-style pictures – beggars and musicians and urchins on the streets of Paris, London and Barcelona – have the candid precision of a National Geographic spread. Her nudes are playful, striking and sexy.

And that was just her getting started. The real gems are the surrealist pictures that would follow. She was a master of her craft, painstakingly manipulating photographic negatives – double exposing, overlaying – to create strange, hybrid images.

Look carefully and you can see recurring characters. A young boy playing in the street in Barcelona later appears under a table in a posh study, hiding, perhaps, from the topless woman riding a man like a donkey. In another picture a child dangles terrifyingly from a wall like the girl from The Exorcist. Look closely and you might recognise him as the boy bending over backwards in an earlier picture.

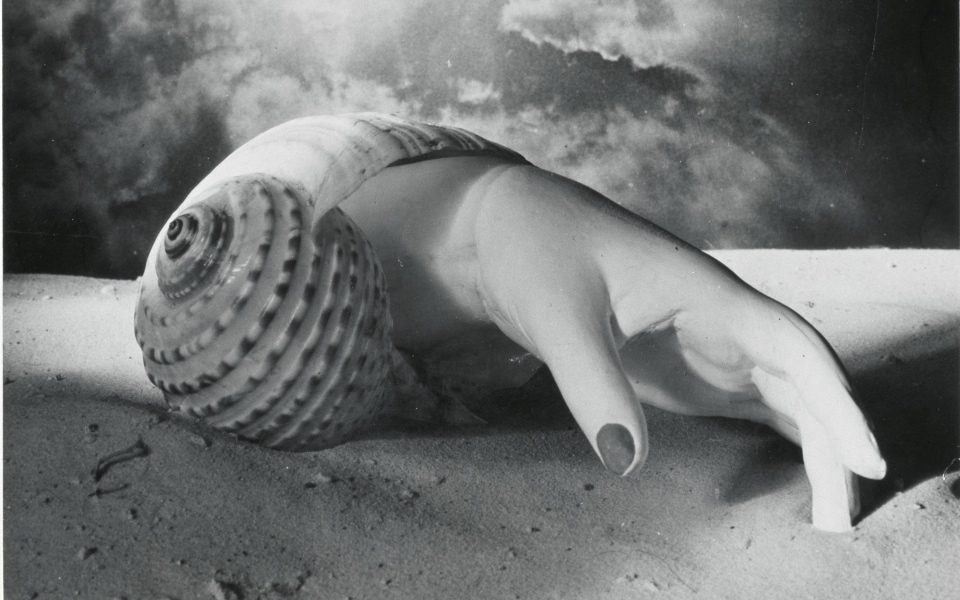

Other pieces are more straightforwardly surrealist, a movement to which she increasingly subscribed. There’s the picture of a manicured woman’s hand lolling from the mouth of a shell, or the close-up of a bizarre animal she refused to name, but which is now understood to be the foetus of an armadillo.

And then she met Picasso, who you could argue was responsible for the least interesting part of her oeuvre. During their affair, which took place while he was with Marie-Thérèse Walter (Picasso even painted an uneasy portrait of the two of them, sitting side by side but facing opposite directions), he encouraged Maar to start painting again, while in exchange she taught him the intricacies of photography.

But her paintings aren’t a patch on her photographs, her abstract landscapes feeling like the experiments of an artist in the making, rather than one who’s already arrived.

When Picasso painted her as the famous green-faced Weeping Woman (a title that sums up their torrid relationship, by all accounts), Maar was relegated to the position of ‘artist’s muse’ rather than ‘artist’.

But this show proves otherwise. Maar continued to work long after Picasso had rampaged into some other poor girl’s life, creating “cameraless” photographs – otherworldly images burned directly onto negatives. Like much of her work, they combine technical mastery with a singular, playful artistiry. Maar is a woman in the shadow of nobody.